© Kevin Moloney

As a photojournalist I once spent several off-and-on years documenting the rise of pentecostalism in Latin America. Lately that situation looks a lot like the state of journalism, its public and the arguments of some journalists about it.

© Kevin Moloney

Once the stronghold of the Roman Catholic Church, Latin America is turning Protestant. There people have been flocking for decades to upstart Protestant churches, particularly pentecostal ones. There are many and complicated reasons for this, but among them is that these little upstarts seem to directly address the needs of their communities. First they put churches in accessible locations like old movie theaters and storefronts in low-income neighborhoods. Then they provide daycare and job training to their congregations which are made up in significant numbers by single mothers. And by letting those congregations in on the service’s conversation they inspire a deep engagement with that community and its leaders. Services there are interactive and passionate by any observer’s measure.

© Kevin Moloney

By contrast, the old-line Catholic churches there tend to be centered around big, elaborate and baroque structures in the center of the cities where they are three bus transfers from the homes of the people they most hope to serve. On their altars are priests — mostly foreigners — who deliver pretty much the same information as the insurgent churches, but with a time-worn and emotionless demeanor. The pews are nearly empty and those sitting in them are mostly the elderly. Like many Catholic priests around the world, they remind the newcomers who show up on Christmas or Easter that they will go to hell if they don’t attend every Sunday.

Both kinds of church offer the same basic story, and both believe that this information is critical for the wellbeing of their congregations. It’s just the style of delivery that’s different, but the results have culture-changing impact on a continent where the Catholic tradition and local culture are deeply intertwined. “They are destroying Brazilian culture,” an anthropologist once told me. “You’re not supposed to samba if you’re a member of one of these churches.”

For journalists (like me) journalism is a religion too. Like other religions it has a long history, dogma, ritual, and a well-formed system of ethics that helps us structure what we say and how we act. We are passionate about what we do and the information we deliver, and we truly believe that it is something society needs to prevent it from going to hell. For us it is a vocation rather than a simple profession.

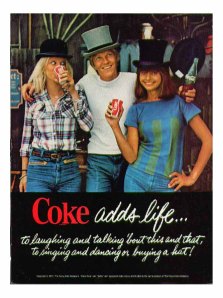

But as we too often rest on the value of our information alone, other media industries are breaking loose of their dogma and reinventing how they tell their stories. Hollywood, Madison Avenue and even Tin Pan Alley have thoroughly broadened their approach to storytelling in the entertainment and advertising industries. They, like those Latin pentecostal churches, are much more fleet of foot and open to what their publics are looking for in the 21st century than we in journalism might be.

© Kevin Moloney

If journalists are the clerics of their religion, then they are like the Catholic priests you find today standing at the altar of a 300-year-old Latin American cathedral, preaching to a congregation of five. And those five congregants are all old and will die sooner than later.

But in the suburb not far away is the Hollywood Megachurch which, despite its own problems, has figured out how to reach people in ways they can use: a more convenient location, effusive passion and direct dealing with the issues that concern the congregation. They embrace and perfect the use of new technologies with early-adopter fervor, and as a result their multiplex pews are full to bursting.

© Kevin Moloney

A few blocks away the Madison Avenue Evangelical Church has learned how to send out its evangelists and better grab the attention of potential converts. And they are reeling in the young and cynical with surprising and innovative new messages preached in surprising places.

And over on Tin Pan Alley the old-line pentecostal temple, after years of losing its congregation to free and easy online gospels, is figuring out how to compel people back with a more tailored, interesting and varietal outreach, and lower tithing.

Back downtown at the Cathedral of the Immaculate Information, our news priest is standing there wondering why nobody is paying attention anymore and telling anyone who walks in that they will go to hell if they don’t show up every Sunday.

All hope is not lost, however.

© Kevin Moloney

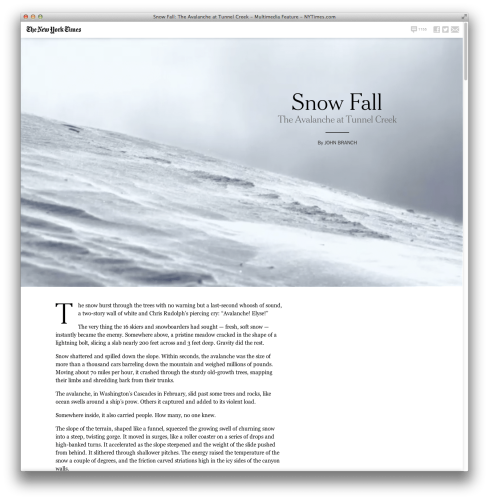

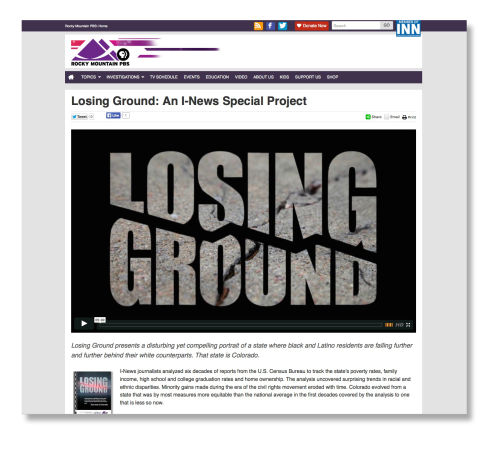

There is a real priest I photographed in São Paulo, Brazil, on that extended documentary a few years ago. Padre Marcelo Rossi is a former aerobics instructor turned Catholic priest who brought not only a youthful and effusive passion to his work, but he learned quickly — like his counterparts at the other churches — to use any medium available to spread his message, particularly ones that land straight in the path of his young target public.

© Kevin Moloney

From early in his career Padre Marcelo was doing radio shows and TV broadcasts, and releasing CDs and videos. He has acted in movies and his multiple Twitter feeds have more than 100,000 followers. At the time I covered him he attracted up to 10,000 people to weekday morning masses, many of whom were school kids who had cut class to go to church. His new sanctuary can hold 100,000.

That’s what we need in journalism. Like Padre Marcelo who changed nothing of the ritual, message or ethics of the Catholic religion but is drawing the crowd, we in journalism don’t need to sacrifice our standards at all. We simply need to stop waiting around the Cathedral for the congregation to show up on our bossy old terms and reach out to the public on its terms. We need to use the media people are paying attention to now and leave our message in the paths they already travel.

© Kevin Moloney

In an old religion like journalism, adaptation to different circumstances can be hard for true believers to take. But like the Catholics of Brazil, losing congregations to more fleet-footed houses of worship, we need to stop insisting on certain patterns of message delivery and look for ways to get our message out in more compelling ways.

There are certainly thinkers in journalism who are as creative as Padre Marcelo is in Brazil’s Catholic Church. They are hard at work like he is to reach out to people on terms that draw them to the story he feels is so important. But many of us journalists, true believers that we are, can’t fathom the massive change under our feet. All we seem to muster is an argument that our information is important to the functioning of the democracy, and you should read it like a good citizen and pay for your newspaper to fund it.

I, too, believe our information is critical and will save you from things like climate change hellfire and political damnation. But journalism suffers from what pressthinker Jay Rosen argues is a “wicked problem.” That means there is no one clear answer, and from the varying perspectives of all interested parties, the problem looks very different. Arguing for its value alone and waiting around for the public to come to us is about as valuable as the “come every Sunday or you’ll go to hell” argument offered from altars around the world on major holidays. However, very creative thinking and borrowing sensible ideas from the media industries across town is a start on shoring up the foundation of this grand old journalism cathedral.

“Priests aren’t showmen,” Archbishop Odilo Scherer of São Paulo once said in a clear reference to Padre Marcelo. “The Mass is not to be transformed into a show.”

Sound familiar?

Transmedia entertainment continues to grow. The transmedia-native

Transmedia entertainment continues to grow. The transmedia-native