The Creative Projects lab at the Center for Emerging Media Design and Development at Ball State University.

You now have an easy way to sample what we offer at the Center for Emerging Media Design and Development. We’ll be offering a trio of online training sessions through MediaShift‘s DigitalEd platform that showcase the center’s three-pronged approach to 21st-century communication design.

Design Thinking — November 29, 2017, 1:00 PM EST

Understanding and solving complex strategic communication problems

Design thinking is a people-centered approach to problem solving that encourages collaborative brainstorming and diverse ideation through systematic strategies and processes. Used in a variety of fields, from product design to web development, design thinking serves as a powerful model for flexible and dynamic critical thinking that puts the audience/user at the center of idea generation.

In this session, Dr. Jennifer Palilonis will share a number of design thinking strategies and explain how they can be used by communication and media professionals to inspire innovative, engaging approaches to storytelling. Dr. Palilonis will also share how she has used design thinking in a number of diverse projects, from working with USA Volleyball to promote the growth of boys’ and men’s volleyball nationwide, to developing a digital literacy curriculum for K-3 students.

Transmedia Storytelling — December 13, 2017, 1:00 PM EST

The mediascape of the 21st century is both a wicked problem and an unlimited opportunity for journalists. At the same time that powerful new storytelling tools have emerged our once-captive audiences have scattered into a dispersed mediascape. We can tell compelling stories like never before. But how do we get those stories in front of the publics that need them?

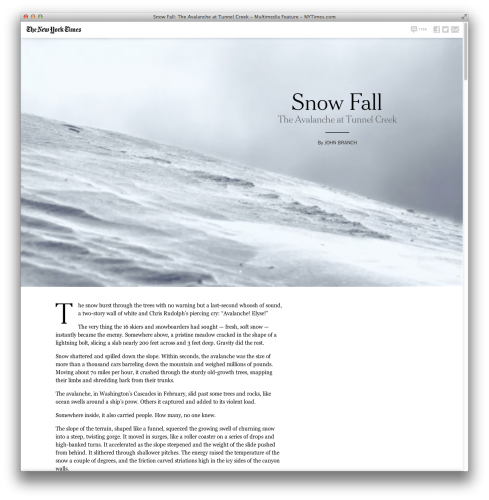

A transmedia story unfolds in multiple media forms and across many media channels in an expansive rather than redundant way. In this training Dr. Kevin Moloney will examine how Hollywood, Madison Avenue and journalism organizations like National Geographic and The Marshall Project use it to tell better and more complex stories and to reach audiences on the media they already use. We’ll talk about tools for finding those audiences, how to build reporting and publishing partnerships, and the decisions involved in transmedia project design.

User Experience Testing — December 20, 2017, 1:00 PM EST

The rapid pace of technological change drives not only more innovative approaches to storytelling but also new behaviors among story consumers. Understanding how audiences experience media platforms and the stories they deliver is one key to retaining and growing them in a shifting media landscape.

Applied in a wide-range of professions toward goals as diverse as the design of new digital products and improving hospital patient outcomes, user experience testing is an approach to understanding what audiences do and why they do it in order to adapt to their needs and leverage their behaviors. In this training Megan McNames will introduce a number of user experience testing strategies and explain how communication and media professionals can use them to understand readers/users and identify opportunities for growing audiences and engagement with stories. We’ll talk about what user experience testing is and isn’t, which aspects of media platforms and stories can be tested and how to implement tests with an eye toward actionable results.