Jump to:

Previous Page: “Where Journalism Has Gone Before”

Spreadable | Drillable

Continuous and Serial

Diverse and Personal in Viewpoint

Immersive | Extractable

Of Real Worlds | Inspiring to Action

Next page: Building Transmedia Journalism

“There are no new ideas in the world. Only a new arrangement of things.”

— Henri Cartier-Bresson

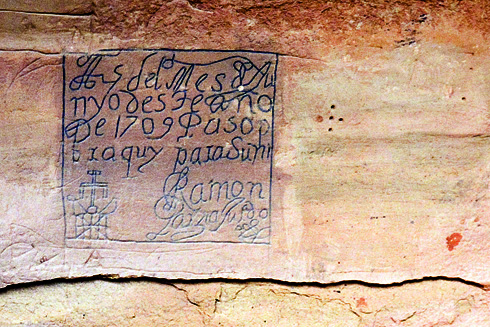

Almost Transmedia

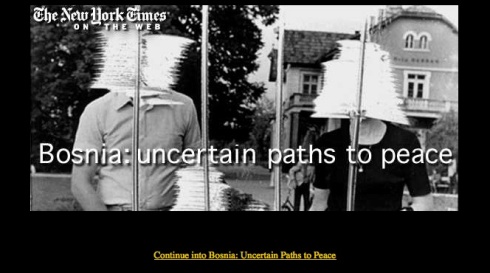

Looking at journalism in terms of Henry Jenkins’ seven principles, all of the characteristics of transmedia as he defines it have individually been implemented in a journalism or documentary context before. Though they may not yet have been designed together in a single storyline, all the pieces of the puzzle are there already. Nothing new must be invented to apply transmedia storytelling in journalism. Many of these principles were accomplished more than 15 years ago in a single complex storyline. For the New York Times on the Web in 1996, photo editor Fred Ritchin and French photojournalist Gilles Peress produced an interactive photo essay that would allow the reader to drill deeper into the the story to see beyond traditional presentation. The result, “Bosnia: Uncertain Paths to Peace,” was multilinear, multimedia and interlinked with contextual information. This essay bears examination on its own for the ideas it implemented at such an early stage. Ritchin described it in his book After Photography:

In our construction, readers would be required to size up the information presented, then take trips and side trips through photographs, text, sound, video, with the option of extracting themselves at any time from Peress’ essay to go to one of the fourteen forums and participate in various discussions, as well as to consult maps, a bibliography, or a glossary. There would be a copy of the Dayton Peace Accords and links to large numbers of other sites and other archival material provided by the Times and National Public Radio.

“Bosnia: Uncertain Paths to Peace” encouraged drilling for more information, provided personal and diverse alternative viewpoints, and expressed itself across multiple media genres. “The intent was also to take advantage of the new strategies made possible by the Web — nonlinear narratives, discussion groups, contextualizing information, panoramic imaging, the photographer’s reflective voice — rather than imitating a print-based essay.”

Building the site, Ritchin added, took months in order for photographer Peress to contextualize, pair and arrange images for the nonlinear presentation. That was longer than he had spent photographing it, Ritchin noted, and much longer than the two and a half days to edit an eight-page New York Times Magazine piece on the same subject. The photographs and information were analyzed by the two for every possible interpretation to help anticipate the many possible orders of images the readers could find for themselves. The order of images had a linear function, with previous and next buttons, but also had a link for “more.” Clicking on that link or an image itself would upend linearity and take the reader down a new path. Selecting images from a grid display encouraged a personal exploration of the scenes. Navigating the site makes a story personal to each individual reader. “It was not story-telling to the reader,” he said, “ but a collaborative creation of story.”

Discussion was designed into the site from the start — a rarity in online journalism in 1996. Not only did the site feature 14 forums for public discussion, but four Internet terminals were installed at the United Nations in New York and two at The Hague to expand the discussion. The forums were introduced by the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations Madeleine Albright, CNN’s Christiane Amanpour, Soros Foundations president Aryeh Neier and others. “Yet the discussion groups were quickly dominated by some of the most racist and vitriolic comments ever to appear in the New York Times,” Ritchin said. Pro-Serbian commentators argued their side of the story was not being adequately represented, that they were being vilified by the media, or that the New York Times had a pro-Muslim slant. Muslims compared the Serbs to Nazi Germany and Hitler’s wish for Lebensraum. “If 1 million Serbs had died in WWII we wouldn’t be having this problem in Bosnia…” Ritchin concluded, “The discussion groups, despite entreaties for civility from former Times foreign editor Bernard Gwertzman, were so rampantly hostile that a reader could learn more from then than any news report as to how extensive, irrational, and personal the contested claims could be.”

In 1995 and 1996 the New York Times was ready to experiment. “I said that since the Web was new we should try something new,” Ritchin explained. He “gave them a list of ideas and this was one that they thought made the most sense — it was a transitional moment for them, and there was a certain openness that went along with it.” It was, however the first and last of its kind at the Times, and my research thus far has turned up no others. “It’s strange,” Ritchin told me, “but I always thought of the Bosnia project as being a primitive example of what can be done, and all these other projects would follow that would push various ideas more deeply, as well as coming up with very different approaches…” He adds, “basically institutions are very slow to change — if someone else does it (independently) they can then point to its success and do something similar (or even publish the same project) — so another question would be why so few independents are engaging journalism, and the world, differently?”

“Bosnia: Uncertain Paths to Peace” was nominated by the New York Times for a Pulitzer Prize in 1997. But as an entity only of the original New York Times on the Web and not the printed paper, it was ruled ineligible. The project expressed many transmedia ideas before even Hollywood had begun to engage them. It did not cross media platforms from the Web to print, television, radio or anything else, and therefore failed to reach beyond the New York Times’ Web readers. It did, however, engage many of Jenkins’ principles of transmedia storytelling.

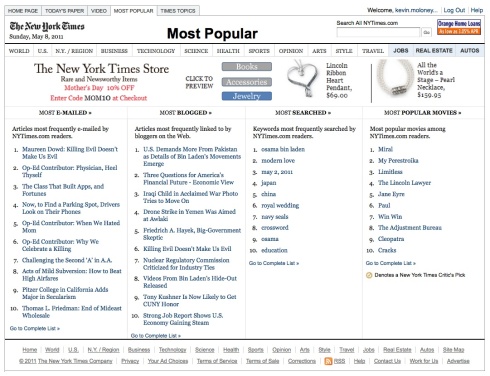

Spreadable

Transmedia storytelling in other kinds of media is driven by the fundamental nature of networked culture: It was invented to seize the advantages of a new mediascape. Despite its often sluggish response to these changes, journalism has not been completely blind to many aspects of networked culture and communication. Spreadability of media, if not at first embraced, is now an element of nearly every journalism production. Visits to the Web sites of nearly any legacy and new media outlet show buttons to share stories and links on social media sites, email, SMS or a blog with a single click. Tracking systems such as the New York Times’ listings of “Most E-mailed,” “Most Viewed” and “Most Blogged” encourage the dissemination of work through the networked sphere by engaging our social instincts further. According to a University of Pennsylvania study of the Times’ Most E-mailed list, stories with positive themes, that inspired awe and dealt with complex subjects were the most often shared. John Tierney wrote in the Times’ own article on the study:

The motivation for mailing these awe-inspiring articles is not as immediately obvious as with other kinds of articles, Dr. Berger said. Sharing recipes or financial tips or medical advice makes sense according to classic economic utility theory: I give you something of practical value in the hope that you’ll someday return the favor. There can also be self-interested reasons for sharing surprising articles: I get to show off how well informed I am by sending news that will shock you.

Though the study did not track other social network sharing, such as links to share through Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn and other services, those too play an important part in any news service’s distribution model. However, legacy media’s interaction with social networking is often as one-way of a conversation as they had with their publics in the last century. Policies such as those announced by the Wall Street Journal in 2009 keep the publication and its employees aloof from the medium by discouraging or disallowing any engagement with the public through those media. Employees of many legacy news media outlets require a journalist’s presence online to be as a representative of the company. The rules also restrict how personal and independent interactions with others can be in the social media space. Sam Ford, a former journalist, MIT blogger and coauthor with Henry Jenkins of the forthcoming book, Spreadable Media, told me, “So much of social media, as these journalists have become more active in the blogosphere, on Twitter, etc., is about expressing your views as you’re working on something or after you’ve completed something.” Policies on social media use by legacy media employees reflect the environment of the last century more than they engage social media on its own strengths.

Aggregators play a part in the spread of media, and for-profit legacy media such as the New York Times have had a difficult relationship with them. Online publications such as the extremely successful Huffington Post repurpose much online news content. In March, 2011, New York Times editor Bill Keller sparked a brief battle of words with Huffington Post founder Arianna Huffington with this description:

The queen of aggregation is, of course, Arianna Huffington, who has discovered that if you take celebrity gossip, adorable kitten videos, posts from unpaid bloggers and news reports from other publications, array them on your Web site and add a left-wing soundtrack, millions of people will come. How great is Huffington’s instinctive genius for aggregation? I once sat beside her on a panel in Los Angeles (on — what else? — The Future of Journalism). I had come prepared with a couple of memorized riffs on media topics, which I duly presented. Afterward we sat down for a joint interview with a local reporter. A moment later I heard one of my riffs issuing verbatim from the mouth of Ms. Huffington. I felt so … aggregated.

Keller’s column in the New York Times Magazine caught a fair share of criticism, arguing that his representation of the Post was unfair and that the Times aggregates content as well. But the brief and high-profile argument illustrated perfectly the uncomfortable relationship much legacy media has with the dynamics of the networked public sphere. Keller also noted in the same column that in the first hour after Hosni Mubarak’s resignation from the presidency of Egypt, traffic to the New York Times Website increased by one million page views. Keller does not reveal the statistics of how that traffic was fed by emailed stories, social networking and news aggregators, but one can assume they played a part in the traffic increase. Like the symbiotic relationship of celebrities and paparazzi, news producers and news aggregators may need each other. With the proliferation of sources of news, a publication can no longer depend on the saturation of its market to ensure it is the go-to news source.

But what, besides being positive, deep and awe-inspiring takes a story from the publication’s own pages, airwaves or Website? Keller himself notes that, “There is no question that in times of momentous news, readers rush to find reliable firsthand witness and seasoned judgment.” Is there a way beyond personal relationships with a publication that leads us to that trust? Several interesting new players in the news mediascape take different tactics to accomplish that. Hypothes.is, Paper.li and News Trust, for example, combine the ideas of spreadable media with the trust that recommendation from members of the public can build. Hypothes.is and Paper.li blend the networked communication of social media with everyone’s will to be a newspaper editor. Paper.li grabs shared links, blog posts and other content from a user’s Twitter and Facebook accounts and aggregates it into a personal newspaper form to be shared with friends and followers. The custom digital newspapers announce to one’s followers what the user finds interesting in what are to them trustworthy sources. News Trust, sponsored by the MacArthur Foundation, allows users to rate the quality of a news story on factors of factuality, fairness and how well sourced it is, among others. In addition to engaging the opinions of readers we may trust, the system works to codify why a story might be trustworthy. “The goal is not only to improve the aggregation process in order to bring together high quality news items but also to engage the community of readers in critically assessing the material, therefore becoming more engaged with it,” writes media scholar Adrienne Russell. The service encourages its users to think like journalists and act like editors.

Spreadable media is a native quality of the networked public sphere, and not new to news media — newspaper and magazine clippings were frequently mailed to friends and family, and posted on refrigerators and bulletin boards. Rarely, if ever, has it been advantageous to hide media content from the view of potential new customers. Like many aspects of the contemporary mediascape it is the ease and speed of sharing that has changed, and with it comes the increased speed of awareness. If at its core journalism is about reporting stories to the larger public, then faster ways of moving that information is advantageous. As Trent Reznor has proved with earlier described examples of spreadable media, the money will follow.

Drillable

There is a mystique to journalism and journalists. A database of the “Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture” contains more than 77,000 references to the appearance of journalists in movies, radio dramas, novels, television episodes and more. Journalists are portrayed as romantically as private investigators, and the two share a common act — digging for powerful information. In 1914 psychologist Alexander Shand described curiosity as an impulse and instinct. It is a “single impulse to know, instinctively governing and sustaining the attention,” he said. Perhaps this is why we are so interested in journalists and gumshoes as pop-culture icons. By making content drillable, content creators and journalists can engage that impulse and help the reader become the reporter.

In entertainment media franchises like The Matrix or Lost, drillability came from incomplete and convoluted stories. This is not a quality journalism could easily embrace. Virtually every reporter or editor working today would shudder at the thought of purposefully obfuscating a story to encourage the public to dig for itself. At the same time, few journalists would argue that the story is ever complete. Information and context are inevitably left out in the process of publishing a concise story. Journalism is a craft of distilling information either to what matters most or what fits the space available. With drillability transmedia journalism will need a different approach.

Using the connected information of electronic databases has provided a simple form of drillability. Hyperlinked words in news stories are now common in many online news media. Reading a text story on sites such as CNN.com, NYTimes.com, or HuffingtonPost.com reveals color-coded hyperlinked words intended to carry the reader to — most often — another piece produced by the same company. In the case of the New York Times, the hyperlinked words often lead to an entry in Times Topics, an encyclopedia-like reference service built from the company’s archive. These links add a degree of context and added information in this form, and are simple to automate. Though more rare, many news sites link to content such as videos, scientific studies and government reports that confirm information in the story. These links act like in-text citations of research material. Still more rarely, hyperlinked words carry the reader to a competitor site for another perspective on the subject. The latter fits more with this proposed idea of drillability.

In “Bosnia: Uncertain Paths to Peace,” Ritchin, Peress and other New York Times on the Web editors provided a sizable set of context links for those wishing to investigate further or learn the history that led to the Bosnian conflict. As it does today, the site first listed stories by the New York Times staff. Following them were links to the work of National Public Radio on the subject, six maps to better illustrate terrain and ethnic divisions, chronologies of the history of the Balkans, and an impressive 47 links to external sources. These ranged from other journalism and photojournalism sites to government agency reports, United Nations agencies, non-governmental organizations, academic sites, missing persons reports and newsgroups. The site provided an impressive story. One reader told Ritchin it took her four hours to explore the site. But in addition an encouraging wealth of information, particularly considering the scope of the Web in 1996, was available for exploration. Its designers showed no fear that its public would be lost to the complex filaments of the Web. Ritchin described the Times’ attitude then as one of “self-confidence.”

In a more recent example, the Washington Post in the summer of 2010 published the results of a two-year investigation of U.S. national security infrastructure. “Top Secret America” involved more than a dozen reporters, editors, designers and bloggers from the Post who collected and digested information about American security agencies and their contractors. They assembled it into a vast relational database designed to illustrate the size of an industry that they argue is tantamount to a fourth branch of government. The story, which ran in series starting on July 19, 2010, featured written stories, photographs, videos and interactive Web graphics built to explore the incredibly complex relationships between the agencies and contractors involved. The complexity of the subject lends itself to a deeper transmedia implementation. The interactive graphics attached to the story on the Web site do illustrate another option in drillability. Exploring the ways in which agencies and corporations, federal, state and local governments and geographic locations are interconnected seizes our interest in exploration. Our instinct to investigate is rewarded with discoveries made from our own actions.

In the context of the standards of journalism, drillability must have a slightly different nature. It would certainly be possible to — as the Wachowski brothers did with The Matrix — plant hidden seeds of information throughout the mediascape to appeal to the natural gumshoes in the public sphere. But these bits of information could not be critical to the story as they often are in entertainment transmedia. In journalism the best implementation of drillability is through hyperlinking more deeply to related information on and off the organization’s own pages. “Top Secret America” embraced the power and depth of interactive databases. “Bosnia: Uncertain Paths to Peace” linked contextual information in a sidebar that offers a first step into the outlying complexities of a story.

Continuous and Serial

A staff project like that of the Washington Post makes continuity much simpler. Whereas in transmedia entertainment “continuity” is the goal of making many possible incarnations of a story align over time and across media, in journalism it is more continuity of editorial approach and style. No matter the medium of delivery, a “continuous” story maintains cohesive history and character. This is probably best accomplished with the work of a coordinated group of journalists, such as the staff of a major media outlet. But it is also possible with the work of a well-coordinated group of individuals contributing to a cohesive body of work.

One example is Luceo Images, a cooperative of seven photographers scattered across the country, with one based in Southeast Asia. The cooperative shares the workload of business operation and marketing, and has recently joined forces on a cooperative series of stories on the issues faced by American small towns. According to cofounder Matt Slaby, a subset of the group has already photographed towns in Nebraska, Kansas and Arizona and plans to document four more towns this year while traveling as a group in a rented recreational vehicle. In each case the group will assemble several of their members and work simultaneously to document issues such as healthcare, education, environmental justice, resource management and repurposing the rural economy. By working simultaneously on the project, the group will more easily maintain a cohesive editorial vision. The continuity of the work will also persist despite medium. Though the primary medium of delivery will be gallery walls, the work will also be proposed to news media as individual stories on the themes they plan to cover and assemble in multimedia and video form for the Web.

The Luceo Images project, like much journalism, will unfold in series. Serial stories have been a fixture of journalism from its earliest days and many of its most notable and praiseworthy works have unfolded in the media over time. Prime examples include the Washington Post’s “Top Secret America” project, which was released over three parts in July 2010, with a fourth appearing in December, as well as the paper’s historic coverage of Watergate which was a two-year investigation. Series stories have won Pulitzer Prizes for many newspapers, including the Denver Post, which won the feature photography award in 2010 for a series that followed Army recruit Ian Fisher from high school through deployment to Iraq.

An important quality of transmedia storytelling is that diversity of media. Reaching potential publics where they dwell provides an opportunity to rethink what is a journalistic medium. Luceo’s use of gallery walls is not new, but it is less common than publishing journalism work in legacy news media both online and off. Arguably, a gallery will attract a somewhat different public than a weekly news magazine, a documentary Web publication or a newspaper. Work in periodicals can seem disposable, destined to ‘line the birdcage’ the next day, whereas a gallery exhibition or a book implies permanence due to the durability of the media. Journalism does not have to live only on its traditional airwaves and pages. Other examples I argue are worth consideration in delivering journalistic content might include institutional museums where journalism content could be displayed alongside physical artifacts related to the story, or as lecture by the producing journalists where the telling of the story can be customized to the needs and interests of the audience. Mark Twain, once a journalist, was a prolific storyteller to audiences. Literary journalist John Reed, who wrote extensively about the U.S. communist movement and the Russian Revolution was a frequent public lecturer on these subjects.

An important quality of transmedia storytelling is that diversity of media. Reaching potential publics where they dwell provides an opportunity to rethink what is a journalistic medium. Luceo’s use of gallery walls is not new, but it is less common than publishing journalism work in legacy news media both online and off. Arguably, a gallery will attract a somewhat different public than a weekly news magazine, a documentary Web publication or a newspaper. Work in periodicals can seem disposable, destined to ‘line the birdcage’ the next day, whereas a gallery exhibition or a book implies permanence due to the durability of the media. Journalism does not have to live only on its traditional airwaves and pages. Other examples I argue are worth consideration in delivering journalistic content might include institutional museums where journalism content could be displayed alongside physical artifacts related to the story, or as lecture by the producing journalists where the telling of the story can be customized to the needs and interests of the audience. Mark Twain, once a journalist, was a prolific storyteller to audiences. Literary journalist John Reed, who wrote extensively about the U.S. communist movement and the Russian Revolution was a frequent public lecturer on these subjects.

Luceo's one-of-a kind artifact book. © Luceo Images

And both to fund Luceo’s Few and Far Between project on rural America as well as explore other media, the cooperative produced for sale a one-of-a-kind book containing one-off instant camera images as well as artifacts from the project’s excursions.

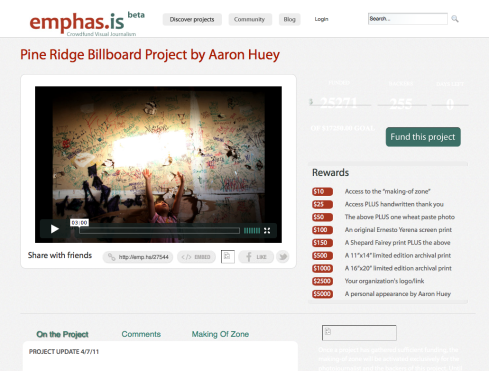

Another interesting example of moving content onto new platforms is Aaron Huey’s Pine Ridge Billboard project. After six years of documenting the Pine Ridge Lakota Sioux reservation in South Dakota, Huey has partnered with artists Ernesto Yerena and Shepard Fairey to create billboards from his photographic work to spread his story of poverty and disenfranchisement on the reservation. This medium pairs with the prior publishing of Huey’s work in legacy news media.

Yet another medium used in entertainment transmedia that has a fledgeling presence in journalism is nonfiction comics. Through the last century, panel-illustrated long-form stories have moved from the earliest Superman comics to the ‘graphic novel’ which takes the comic illustration form into artistically deeper territory. Several acclaimed examples of journalism nonfiction comics have appeared recently. Joe Sacco won an American Book Award for Palestine, a long-form graphic journalism book on the life and plight of Palestinians. He also published a book on the Bosnian war, Safe Area Goražde, and another on the Gaza Strip, Footnotes in Gaza. Sacco finds the medium advantageous in telling a historic story. He told Al Jazeera of the Gaza book, “It has a certain strength in that it can take you back in time and it can drop you in a place. I can really set the reader right in Rafah or Khan Yunis and I can do it in the 1950s or in the present day. There is an immediate connection with Gaza when you open the book.” Another nonfiction comic author who uses the medium as one in a small array of media to tell a story is Josh Neufeld, who began a project on post-Katrina New Orleans by serializing his work in the online magazine Smith. In 2009 his work was published as A.D. New Orleans After the Deluge. Neufeld’s nonfiction comic piece is illustrated from interviews with Katrina survivors on their experiences before, during and after the storm. “My first role as writer/artist of ‘A.D.’ was that of a journalist, finding subjects for the story,” he writes. Neufeld’s work features the stories of seven survivors, and panels were built from interviews, reference photographs and multiple visits to the scenes in the story. The Web version of the story on SMITH magazine’s site features links to podcasts, videos, archived hurricane tracking reports and personal details like one character’s favorite mixed drink recipes. All of these projects demonstrate the power and advantage to thinking of journalism beyond media boundaries to reach wider and more diverse publics, and in series to keep them intrigued and engaged over time.

Diverse and Personal in Viewpoint

In addition to continuity through a coordinated and shared subject, the Luceo Images small-town America project uses multiplicity. The photographers engaged in the project all view the same subject from naturally individual points of view. As four or five of the cooperative’s members fan out across a subject town, they bring their individualism to a group effort. If Thomas Nagel’s “view from nowhere” idea of journalistic objectivity is functionally impossible, then this form of multiplicity changes the shape of reporting. If a reporter’s background, history and opinions are never divorced from his or her work, then adding multiple reporting voices brings a broader view on a subject.

This can be achieved by methods like Luceo’s as well as by linking to outside news sources on the same subject, as was done by the creators of the “Bosnia: Uncertain Paths to Peace” project by the New York Times. The technique used in the Bosnia piece is not a new one to bloggers, who frequently add context and perspective to their work with links to external reporting, and it is even older in academia where in-text cites and bibliographic information are de rigueur. In 2008, journalist and blogger Jeff Jarvis defined link journalism: “The standard journalistic technique for providing context and support for assertions is to quote sources, but on the web, the ‘link journalism approach’ is to link to other actual reporting.” (Emphasis in the original) Jarvis also addressed a concern that might be at the top of the minds of journalism publishers who hope to keep their publics contained on their own sites: “Oh, speaking of traffic, what about the concern that link journalism will ‘send people away’ from a newsroom’s own original reporting? Just remember Google’s law of links on the web — the better job you do at sending people away, the more they come back.”

According to a 2009 study by the Pew Research Center for the People & the Press, only 29 percent of Americans say news organizations get the facts straight, while 63 percent regard news stories as often inaccurate. Writing in Nieman Reports, former journalist and media studies scholar John McManus argued that diverse perspectives from both media professionals and the public would help journalism’s trust and transparency issues:

Rather than pretending that they cover “all the news that’s fit to print,” providers would have to acknowledge their limitations of staff and space or time and invite the public as a partner in what would be a more empowering and democratic form of journalism. Now is the time. As news moves to the Web, it can more easily accommodate give and take with the community it serves. There’s room for diverse perspectives. Updates and revisions are easy to accomplish. And news is easier than ever to share.

McManus derived his argument partially from sociologist Herbert Gans, who in his 1979 book Deciding What’s News called for news from multiple perspectives. In an interview with NYU’s Jay Rosen, Gans described it as, “reporting all ideas that could resolve issues and help problems, even if the ideas come from ideologically small groups.”

Gans’ “multipersectivalism” applies not only to link journalism as mentioned above, but to the notion of opening the journalism conversation to the public as well. Citizen comment and citizen journalism reflect not only Jenkins’ principle of multiplicity, but also subjectivity. Reader comments are now as an entrenched feature of professional journalism sites as they are of amateur media and blogs. The vitriol that seemed to surprise Ritchin and the Web producers of the New York Times in 1996 are part of the journalism landscape. Though allowing public comment on stories is a step closer to Gans’ ideal, many argue that the American news media has remained aloof to the public discourse. Responses by journalists to comments are rare, and interaction about the reporting or editing of a story is even more rare. Spreadable Media coauthor and former MIT blogger Sam Ford pointed out to me, “A newspaper story goes up (on the Web) and you have a lot of discussion, debate, comment and response, and never, almost ever, do you hear from the reporter again.” Ford and others argue that by opening journalism to comment, the media need to enter that conversation directly rather than saying, ‘now talk among yourselves.’ Interestingly, PBS uses that phrase exactly on it’s Five Good Answers series of blog posts that interview PBS reporters. “Want to continue the conversation? Use the ‘Comments’ section beneath this entry. Feel free to talk among yourselves.”

Citizen journalism advocates also point to the advantages of citizen contribution to news. Media studies scholar and journalist Dan Gillmor, Jay Rosen and others advocate embracing a native function of the Internet age provided by the extremely low cost of entry to publishing. As Gillmor noted in a Guardian article, “We would invite our audience to participate in the journalism process, in a variety of ways that included crowdsourcing, audience blogging, wikis and many other techniques. We’d make it clear that we’re not looking for free labour – and will work to create a system that rewards contributors beyond a pat on the back – but want above all to promote a multi-directional flow of news and information in which the audience plays a vital role.” Citizen journalism is multifaceted, much debated and complex. Gillmor himself breaks that simple article on the subject into 22 different rules of engagement. By whatever means it both adds Gans’ multiperspectives into the news and allows for the public ways to express its own view of the story.

New systems are emerging to embrace the idea of public news remix and repurposing. Media and immersive journalism scholar and journalist Nonny de la Peña is one of the creators of Stroome.com, a collaborative video editing system. The project has several goals, from providing to a public that cannot normally afford expensive authoring tools a browser-based platform for editing content, to fostering collaborative content production and content remixing. It has a history in the legacy media, as she tells Henry Jenkins in an interview:

Remix is an old culture in newsweekly journalism. For example, as a correspondent for Newsweek, I would join other Newsweek correspondents around the world in contributing material for a single story. We would all send in our individual reports to headquarters in New York where a “writer” would edit our material into the piece that would appear in the magazine. Stroome is based on the same principles. Multiple people can contribute to one story by uploading their video onto Stroome and it can be remixed right in the browser into a finished piece that can be quickly shared across the web. Stroome pushes the newsweekly idea even further, creating a social networking site that celebrates what’s possible on the web today. Multiple people can remix any story and that means any contributor can choose to have a voice on how the story should be told.

The Stroome system was relaunched in April, 2011 with user interface improvements sponsored by the Knight Foundation with a Knight News Challenge Grant. And though de la Peña considers it a journalism tool, it has so far been embraced globally by users of all interests.

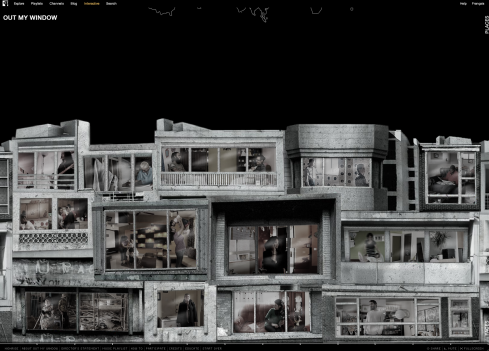

Jenkins’ transmedia principle of subjectivity, where a story is told through the eyes of different characters within that story, is also a time-honored technique in journalism. In radio many notable documentary projects have been produced by providing a subject with a recorder to report on his or her own life. The technique has appeared in regular shows like NPR’s Radio Diaries, but perhaps most notably in Ghetto Life 101, a documentary by radio producer David Isay in which two 14-year-old boys recorded their own lives in one of Chicago’s worst housing projects. Closer to transmedia is the Canadian National Film Board’s nonlinear and multimedia presentation Out My Window, which examines life in the world’s high-rise buildings through the first-person voices of the residents themselves. The nonlinear presentation encourages an interactive and drillable exploration of the lives of the subjects in 49 stories about 13 cities told in 13 languages. The project in 2011 won an International Digital Emmy Award for nonfiction.

Followthrough has long been a weakness of traditional journalism. From my own experience I remember watching many stories reported early in their progression, but without closure after that story was resolved. Perhaps a person was arrested for driving under the influence, and though the arrest was reported, the ultimate disposition of the case was not. Sam Ford noted, “It’s something that transmedia might help answer: the number of dropped stories that any publication has. We hear the launch of something but then we never hear how that something went six months down the line.” This issue exists largely because journalism is time consuming, staff is limited and the next day the attention is on a new story. By opening the doors of journalism to the public, problems of followthrough may be corrected by the public itself.

Immersive

Drawing the public into a story is a long-time goal of journalism. Writers — from those constrained by the time and space of the newspaper story to long-form literary journalists — work to build mental images of the world on which they are reporting. Former Chicago Tribune correspondent Laurie Goering explained to me years ago that an old editor she respected once asked her to “tell me how it smelled” to get her to think of making those mental images in the reader’s mind. Visual storytellers set scenes in a space to help the public break Diderot’s ‘fourth wall’ and help the viewers through the proscenium or the screen.

Games provide one way for the members of the public to immerse themselves in a story through action and first-person emotion. Games also illustrate how a system works better than anything else. Games as a method for experiencing a piece of the news are also starting to appear more frequently. Examples of ”news games” include Wired magazine’s “Cutthroat Capitalism,” a game that accompanied a piece on Somali pirate raids. Game design professor Ian Bogost of the Georgia Institute of Technology described it: “A smart player will rarely fail — and that is the strongest rhetorical point presented in the negotiation process. If a ship can be captured, its hostages and cargo are always worth something.” (Emphasis in the original) The point of the game is to show the economic incentives of piracy in an engaging, first-person manner. “Games allow us to address systems instead of stories,” Bogost told The Atlantic in an interview. “In particular, they can offer this experience of how something works rather than a description of key events and players.” Games continue to build clout as a reporting tool. The New York Times in 2007 published on the Web several games created by Bogost and his Persuasive Games designers, and a new game is anticipated from the Times in 2011.

Through online distribution, games can easily be attached to a journalism project or series of news items, they do not need to be online exclusively. USC researcher Nonny de la Peña is currently working on a board game to tell part of the story of the California eugenics movement of the 1930s. “How does this happen? How do people do this to each other?” are the questions she hopes the game asks. In the game players must answer actual IQ questions from the era that she’s says are clearly culturally specific. If your game play partner answers three questions wrong they become “unfit” and you send them to a sterilization camp in Sonoma. “It’s about the money,” she told me. “The whole system is about the unfit, and the unfit were going to waste the money of the society… and this is how much money…” The game debuted at the 2011 Games for Change conference in New York.

Alternate reality games, in which players move themselves through the real world in pursuit of game goals, are also turning up in journalism. In 2009 the Rochester Democrat & Chronicle partnered with the Rochester Institute of Technology to build a city-wide alternate reality game (ARG). “Picture the Impossible” was a game intended to attract and engage Rochester citizens under 40, a demographic they felt they weren’t reaching. More than one thousand team-organized players scanned the paper’s content — from text to photos, crosswords and online features — in a scavenger hunt that took them through the city’s history. Though it wasn’t directly news related, the success of the experiment has caught the attention of the newspaper’s managers. “A hundred years ago, putting news in a newspaper caused people to take action in certain ways,” managing editor for content and digital platforms Traci Bauer told the Nieman Journalism Lab in an interview. “That doesn’t seem to motivate people under 40. The people who write letters to the editor to newspapers aren’t people under 40, they’re people in their 60s. That’s no longer the way to get people to use information and act accordingly.”

Nonny de la Peña, Peggy Weil and others have also been experimenting with ways to make journalism more immersive. They write:

The fundamental idea of immersive journalism is to allow the participant, typically represented as a digital avatar, to actually enter a virtually recreated scenario representing the news story. The sense of presence obtained through an immersive system … affords the participant unprecedented access to the sights and sounds, and possibly feelings and emotions, that accompany the news.

De la Peña equates the experience to “being there” where the visitor can interact with the environment around them and investigate the context of the news, so long as the environment is grounded in the real world.

As technology advances, so do the possibilities for deeper immersion and allowing the public to feel the scene for itself. In 2007 de la Peña and collaborator Peggy Weil built a virtual Guantanamo Bay prison camp in the online virtual world Second Life. There visitors could experience the life of a detainee based on recorded interviews with former detainees. In the virtual space those videos play on screens around the camp. The user’s avatar is hooded and strapped to the floor of a military transport plane then released into a cage in the camp. The user’s avatar is unable to move beyond the cage in the Second Life virtual space, but your avatar is not tortured. “Rather than a torture chamber, we elected to build a contemplation chamber,” Weil said. “A series of spaces to report and contemplate the practices going on in Guantanamo, as well as the current news via RSS feed.”

The project is not the first nor the only by the two. They have previously collaborated on immersive pieces designed to help the public understand the price of carbon consumption and a piece based on the interrogation logs of Iraq war detainees. In the latter the user finds him- or herself in a stress position used in U.S. detainment camps. Though not actually in the physical position, virtual mirrors showing the user’s avatar in that position resulted in accelerated breathing and a sense of discomfort in its meat space participants. “You know where are your legs and your hands but at the same time you see the other guy, the guy that is supposed to be you, and you look at him and… OK I’m really flexed, I’m in an uncomfortable position, so you start to believe that you are him,” related one study participant interviewed about his experience. “The over-arching intention was to apply best practices of journalism and reportage to this unique 3D space to intensify the participant’s involvement with the events,” de la Peña and her collaborators wrote.

De la Peña and Weil are currently working on an immersive journalism piece to accompany a USC multimedia documentary project, “Hunger in the Golden State.” The site explores multiple aspects of the problems of hunger, food production and distribution and food waste in California. Taking a real reported event in which a food bank recipient slipped into a diabetic coma while waiting in line for food, de la Peña and Weil plan to build an immersive experience in which users will find themselves in that line, forced to react to the event. The production would use actual audio of the event to build the scene. The audio is “pretty amazing,” de la Peña said. “You’re really there in the line and they’re calling out numbers and it’s chaotic.”

De la Peña notes that immersive journalism has its critics, particularly about the inherent subjectivity of participation. But journalism’s best practices and transparency are the keys, she says. “If we can point to our sources, provide excellent research and be open to comment and criticism, immersive journalism can live up to its potential. In a sense, it’s simply about applying traditional journalistic principles to the new technologies.” And as James Cameron’s Avatar raised the technological bar for Hollywood beyond the reach of amateur producers, so might immersive journalism technologies for journalism. “As far as major journalism organizations should be concerned,” she told me, “immersive journalism gives them back their authority, their editorial control… all of those things they just really miss.”

Extractable

What can the public take from the news and put to use in its daily life? In the entertainment media this usually means items, from Eskimo Pies to Han Solo action figures. But journalism does not usually merchandise in the same way. One answer to this principle is, of course, the idea that the information we receive from news sources changes our everyday actions and engages us in the community. But as Traci Bauer of the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle noted above, “That’s no longer the way to get people to use their information accordingly.” To answer this goal, the newspaper launched a game, and I argue that games are a compelling option for the public to extract from journalism and take into their daily lives. A compelling game or immersive experience can long outlive the news cycle, keeping the public in tune with news events long after the media have moved on to the next event.

Souvenirs are not strangers to journalism. They may come in the form of souvenir and special editions of newspapers like those from the wedding of Britain’s Prince William and Kate Middleton, or the reprinted editions of historic newspapers, staff-written books and unrelated items offered by The New York Times online store. Extractability in this sense should be meaningful. What the public should take away should match the ideals of the journalistic endeavor and provide personal and enlightened value.

An answer offered by two recent digital entities is “connection.” With declining newsroom budgets, many journalists are looking to crowdfunding to subsidize reporting of expensive stories. Kickstarter is one of the oldest, and though it is used by more than journalists, many have funded projects through its system. At this writing 269 projects use “journalism” as a keyword. A newer entry is Emphas.is, a system specific to visual journalism projects. Both entities use all-or-nothing models to fund a project. The person or project wishing funding proposes a budget for the work, and only if that amount is met or exceeded will the project receive its funding. Kickstarter states on its FAQ:

1. It’s less risk for everyone. If you need $5,000, it’s tough having $2,000 and a bunch of people expecting you to complete a $5,000 project. 2. It allows people to test concepts (or conditionally sell stuff) without risk. If you don’t receive the support you want, you’re not compelled to follow through. This is huge! 3. It motivates. If people want to see a project come to life, they’re going to spread the word.

Extractability comes in the form of rewards to the donors, however. Both systems require a proposal to provide a tiered set of rewards to donors who are more motivated by something physical and related to the story. Typical rewards may be as simple as a postcard from the target country or as luxurious as a hard-cover book of the finished work. Emphas.is, in addition to the physical rewards, offers access to the journalist on the ground. Donors receive regular updates on progress from the photojournalist through a blog feed and direct interaction. Before their official launch in March, a teaser screen appeared on the site that read, “‘What if you were on Robert Capa’s email list in 1944? What if Don McCullin was blogging from Vietnam? Now imagine if you’d sent them there yourself.” The questions refer to some of history’s greatest photojournalists in hopes of attracting the medium’s fans through both nostalgia and connection. So far their success has been good. Aaron Huey’s “Pine Ridge Billboard Project” proposed a budget of $17,250, but in the end raised $26,431 from 265 backers. In exchange, backers get communication access to Huey as well as rewards from a handwritten thank you to a Shepard Fairey or photographer’s print, to even a personal appearance by Aaron Huey himself.

Tomas van Houtryve, another Emphas.is photojournalist, raised $10,075 for his $8,800 proposal to travel to Laos in order to finish a seven-year project on communism in the 21st century. Van Houtryve’s backers not only provided money, but on-the-ground contacts for his now-underway project. “I can’t, in good financial conscience, sit on the Internet all day telling people how I work,” van Houtryve told the Emphas.is blog in an interview. “But if I’m paid as a teacher, or if backers are contributing, that’s sustainable, it’s not time lost. And it’s even nicer to be able to do it out in the field, instead of entering an academic structure or setting up a workshop. That’s a golden combination.” Systems like these also offer a reward to the journalist or group undertaking them, adding to the conversation in ways proponents of citizen journalism advocate. “I’m trying to give people a vastly different experience than they would get from a newspaper or magazine website.” he said. “If you post a comment there, no one ever gets back to you, or it often becomes a shouting match with other people leaving comments.”

Not every journalist sees crowdfunding as a silver bullet for funding long-form work, nor as a fair trade for the donor. Luceo Images’ Matt Slaby, told me, “I don’t think that the content itself (and access to it) is what should be privately monetized. To me, in spite of being a contributor to them, they come off as begging on the virtual street corner where the giver gets some token item in exchange for a disproportionate contribution… It’s an interesting idea, but seems like its monetization strategy is working against its marketing efforts.”

Of Real Worlds

Jenkins’ principle of worldbuilding is of significant importance in a transmedia entertainment production. When imagining a new world for a fictional story, all the complexities and nuances must be imagined and created as well. However, journalism and documentary stories already exist within a preexisting world notable for its complexity, nuance and unpredictability. It is not the task of a journalist to build that world, but to explore its many possible stories in the most enlightening way — or to facilitate the public doing that for itself. If journalism has fallen short it is in its effort to simplify and make more approachable issues and events that defy simplification.

A notable example in which the authors strove to move away from standard event-based reporting of the war in Afghanistan in hopes of documenting more of the nuance was the 2010 documentary Restrepo. Directed by photographer Tim Hetherington and writer Sebastian Junger, the film follows a company of U.S. Army soldiers through 14 months of duty in a remote and dangerous valley. The film is not all about action, however. Hetherington describes the goals of the film:

There’s a great emphasis in war reporting on capturing the actual “bang-bang” fighting of war—and many reporters feel that any work would be incomplete without a sense of this “action.” We were no different, but because there was an incredible amount of fighting going on in the Korengal Valley, recording the actual firefights got quite boring. What was infinitely more interesting and revealing was how the soldiers carried on in these situations. People who haven’t experienced war inevitably base their understanding of it [on] the mediated versions of news or Hollywood. These representations are often limited and can’t quite reveal the humor, boredom, and confusion inherent in combat. It’s something we felt was important to represent.

The film received high praise in the media for its portrayal not only of the ‘bang bang’ but of that day-to-day functioning in a combat zone. The film also won the Grand Jury Prize at the Sundance Film Festival and was nominated for an Academy Award. New York Times media writer David Carr said of the film, “…for the most part public interest and understanding of what American soldiers do on our behalf remains remarkably limited in wars that go mostly untelevised and undernoticed. American men and women fight, die and kill a long ways from home, and many want it to stay that way.” Hetherington, it should be noted, was killed in Misrata, Libya, April 20, 2011.

In “Bosnia: Uncertain Paths to Peace” Peress widened the world of the Bosnian conflict by taking the public away from the points of breaking action and into the suburbs of Sarajevo. Once there, images become windows into corners of that world to be wandered at an individual pace and an order that is not predetermined by the publisher. “Any confusion that resulted for the reader seemed minimal compared to the actual chaos in Bosnia,” Ritchin said of the structure. The project, with its massive scale, pulled its public into a world they doubtfully would have entered on their own.

Inspiring to Action

What about journalism inspires the public to action? If journalists enter the profession hoping to inspire change and engage the public in democracy, facilitating a way for the public to act on information is a significant goal. This impulse is as old as journalism itself and has many powerful historic examples. From Jacob Riis’ lengthy and immersive photographic investigation of the slums of New York in 1888 to Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, Woodward and Bernstein’s Watergate investigations and the cumulative photographs of the Viet Nam war, journalism — particularly the long-form variety — has been a vehicle for inspiring change.

- New York, 1888. Jacob Riis.

One example has endured every year for a century. The New York Times Neediest Cases Fund comes from publisher Adolph Ochs himself, who, in 1911, encountered a homeless man to whom he gave a few dollars and his business card. “If you’re looking for a job,” he said, “come see me tomorrow.” The next year the Times began publishing stories of the 100 neediest cases in New York, a tradition that is repeated every year. The program has raised more than $256 million in its hundred-year history.

However, appeals are rarely so direct and journalists themselves hope to inspire action without asking so bluntly for the public to take action. We hope the change will come organically from our work. To that end, Nicholas Kristof, a columnist for the New York Times said in a story for Outside Magazine, “Good people engaging in good causes sometimes feel too pure and sanctified to sink to something as manipulative as marketing, but the result has been that women have been raped when it could have been avoided and children have died of pneumonia unnecessarily — because those stories haven’t resonated with the public.” Kristof argues that journalists, activists and philanthropies all need to work on their message and adopt the methods of marketing:

Any consumer-products company rolling out a brand of toilet paper will agonize over marketing. The messaging will be carefully devised, tested with focus groups, revised based on polling, tested in a particular market, tweaked, and tested again. And that’s for a product whose launch makes no difference for humanity. In contrast, if an aid group is trying to raise support for a new program that could save many lives, it will often rely on a hodgepodge of guilt and statistics that limit its effectiveness. It has been said that “statistics are human beings with the tears dried off.” That’s precisely the problem — all the psychological research shows that we are moved not by statistics but by fresh, wet tears, with a bit of hope glistening below.

Kristof argues that to inspire action journalists must first tell compelling stories about individuals rather than statistics. They could also provide an outlet for action that may actually help that individual. Transmedia storytelling techniques would not only reach wider publics, but provide deeper engagement with the story being told, more context and a conversation about the issue rather than just a lecture.

Next Page: Building transmedia journalism

December 4th, 2011 at 6:30 am

This is an incredible document. Bravo for your detailed research and presentation. Thanks for this. Looking forward to more.

November 27th, 2017 at 1:36 am

New programme

http://interracial.dating.porndairy.in/?stage.rachael

free dating site nigeria absolutely free dating sites no credit card required social media networks best social dating sites jack mormon dating

November 27th, 2017 at 2:38 am

New work

navigation app android free onlinegames mobile racing games for android themes for android for free google games free games

http://apps.android.telrock.org/?stage.melinda

tv apps apk get android 5 1 adult stream sexy babydolls free mario game download

November 27th, 2017 at 3:38 am

Blog with daily sexy pics updates

http://sexypic.erolove.in/?entry.faith

13 nude sxxx janet jackson boob porn tube transexual teens sex video painful teen anal mega tit tube

November 27th, 2017 at 4:39 am

Adult blog with daily updates

mens clothing fashion gay cartoon pron the science encyclopedia

http://sissy.adultnet.in/?page.mariam

flightsto south africa plastic surgeons rhinoplasty russian brides club anatomy of the male urethra become a sissy maid gay web chat rooms adult toy for man womens hosiery

November 27th, 2017 at 9:13 am

My revitalized number

http://arab.girls.tv.yopoint.in/?entry.nataly

bbc thierry psychology tales populous

November 27th, 2017 at 1:48 pm

Started new web predict

http://bbwphotos.sexgalleries.top/?post.elisa

shark loving porn dangerous porn sites toper gay porn star mayara shelson porn porn spywere

November 27th, 2017 at 4:51 pm

Hi reborn website

http://arab.sexy.girls.twiclub.in/?entry-jessie

pascal aghil dec wholesale uae

November 27th, 2017 at 8:30 pm

Hi supplementary project

http://arab.sex.photo.xblog.in/?entry.thalia

sign europeans naming soup upcoming

November 27th, 2017 at 10:20 pm

Study my modish project

find my android phone download free sexy video for mobile android app apk files download tema android video sexy mp3

http://bsdm.apps.android.purplesphere.in/?diagram.noelia

showbox download android app apps android 2 2 best apps mobile aplicaciones para android 2 app shop android

November 28th, 2017 at 2:58 am

Original devise

http://teenbbw.yopoint.in/?leaf.kaylin

erotic reviews youprone video erotic story books korean erotic movies download erotic

November 28th, 2017 at 5:55 am

Original project

http://big.boobies.twiclub.in/?entry.aryanna

montana fishburne porn sextape free ebony and black porh siteteenage sex porn ebony flenstone porn porn brother sister babysitter

November 28th, 2017 at 8:59 am

My novel folio

http://arab.aunties.porndairy.in/?post.kiara

wilder ks2 marketing ru orleans

November 28th, 2017 at 10:20 am

Started untrodden spider’s web project

pc tablet mp4sexy video download download free sex download strip poker android game download free google app

http://adult.google.play.lastnews.in/?diagram.america

tablets for sale android 2 1 games free adult photos free apps for free movies world popular android games

November 28th, 2017 at 10:57 am

Appealing girls posts

http://roleplay.sexblog.pw/?reserved.paola

erotic wallpaper erotic dance videos best erotic books erotic photoshoot

November 28th, 2017 at 12:24 pm

Hi fashionable website

http://dateme.sexblog.pw/?stage.elaina

cam live christian singles view local singles dating for gay be a life coach

November 28th, 2017 at 4:18 pm

Daily updated sissy blog

ШіШ«Ш· ШШ®ШіЩ‡ЩЃЩ‡Ш®ШЇ baby name generator fat lady big ass

http://sissy.adultnet.in/?view.marlee

halloween ideas costumes sissy male stories girls makeup tips why i cheat on my husband online skirt education in south africa erotic subliminal hypnosis is plastic surgery worth it

November 28th, 2017 at 4:32 pm

Blog about sissy life

hair removal devices chastity with sound tourmaster sissy bar bag

http://sissyabuse.blogporn.in/?view.katy

apron french british wedding dress shops for sale durban corset wholesale english word and meaning gender sexism older man young women sex harley davidson big