Jump to:

Previous Page “Contexts”

Next Page: Transmedia Principles

“Once a thing is put in writing, the composition, whatever it may be, drifts all over the place, getting into the hands not only of those who understand it, but equally of those who have no business with it.” — Socrates

Origin Stories

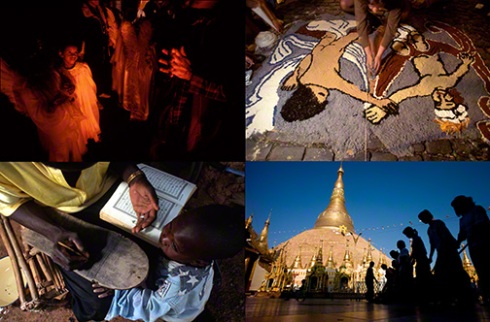

“Transmedia storytelling” is not a new phenomenon, and is perhaps the oldest technique we have for spreading information. From memorized sagas transferred orally from one storyteller to another, to cave paintings and art, the tales told through human history have found multiple channels to their publics. As Henry Jenkins notes, before the age of public literacy, when sacred texts were only readable by a privileged few, religions employed every means available to spread their message. Visits to traditional churches, mosques and temples around the world demonstrate this in their passionate and storytelling art works, sculptures and nonverbal symbols. Origin stories and morality tales express and extend themselves in the costumes of celebration and the talismans of belief. Mythic stories have always found new life, new form and reinvention through the play of children, the imagination of artists and the personal interpretation of listeners and readers. Single-medium communication, of the kind seen through the 19th and 20th centuries, is perhaps an anomaly.

The one-way, exclusive media channels of the 20th century were a creation of economics. The high cost of production and publication kept the imaginative public out of the professional process, but mass media stories never stopped being explored and reimagined by the public. Every mid-20th-century boy with a Davy Crocket coonskin cap, young Zorro with a stick for a sword or little Nancy Drew with an imaginary blue roadster immersed him- or herself into a mythology, extended a story beyond the bounds of its published and copy-protected source through backyard games, handwritten tales, and scrap-paper drawings. They made a practice of all the storytelling techniques of human history, but only very rarely with the economic means to spread those extensions to the wider world.

The one-way, exclusive media channels of the 20th century were a creation of economics. The high cost of production and publication kept the imaginative public out of the professional process, but mass media stories never stopped being explored and reimagined by the public. Every mid-20th-century boy with a Davy Crocket coonskin cap, young Zorro with a stick for a sword or little Nancy Drew with an imaginary blue roadster immersed him- or herself into a mythology, extended a story beyond the bounds of its published and copy-protected source through backyard games, handwritten tales, and scrap-paper drawings. They made a practice of all the storytelling techniques of human history, but only very rarely with the economic means to spread those extensions to the wider world.

The many-to-many form media has taken due to the reduced cost of publishing has also caused conflicts over copyright, visions of what culture should be. Legal scholar and copyright activist Lawrence Lessig argues that the one-to-many mass media model of the 20th century was a stifling of culture and creativity. “Culture moved from a read-write to a read-only existence,” he said in a 2007 TED conference. In making his point that digital technology has moved culture back to a read-write existence, he shows amateur remix videos that became viral phenomena. “The importance of this is not the technique you’ve seen here,” he notes about the work, “because every technique you’ve seen here is something that television and film producers have been able to do for the last 50 years. The importance is that that technique has been democratized. It is now anybody with access to a $1,500 computer who can take sounds and images from the culture around us and use them to say things differently.”

But Lessig is looking only at economics when determining that read-write culture became dormant. He implies that because professional media became so well distributed, amateur culture virtually ceased. However, like most 20th-century mass-consumption children I took the tales fed by Hollywood and the highly filtered book publishers and reimagined and extended those stories in play. I wrote fan fiction, drew doodles on class notebooks, acted in homemade plays with siblings and friends, and eventually made audio recordings and 8mm films. My closest friends and I recorded and rearranged Star Trek episodes on a reel tape deck, and later created and remixed music in garage bands, reinvented comic book heroes in pencil and traded exquisite-corpse prose. We used techniques available to Hollywood for the prior 50 years. What we lacked was an Internet on which to cheaply publish or work collaboratively with distant fellow fans or fellow amateur musicians, artists and storytellers.

L![]() essig implies that technology makes cultural remix possible, and that remix is a deadly challenge to legacy mass media companies. But a technological gap in cultural production has always existed. If new technology allows amateurs to work in ways that match the techniques of Hollywood in previous decades, economics will allow Hollywood to develop new techniques out of the reach of the amateur world. James Cameron’s Avatar, a 2009 science fiction film and transmedia franchise, changed the standard with 3-D filming and animation techniques that are perhaps decades out of reach of Lessig’s middle-class teenaged content creators and their home computers. What has changed is access to the worldwide public. Now Lessig’s middle-class teen can broadcast him- or herself to millions with a few clicks of a mouse.

essig implies that technology makes cultural remix possible, and that remix is a deadly challenge to legacy mass media companies. But a technological gap in cultural production has always existed. If new technology allows amateurs to work in ways that match the techniques of Hollywood in previous decades, economics will allow Hollywood to develop new techniques out of the reach of the amateur world. James Cameron’s Avatar, a 2009 science fiction film and transmedia franchise, changed the standard with 3-D filming and animation techniques that are perhaps decades out of reach of Lessig’s middle-class teenaged content creators and their home computers. What has changed is access to the worldwide public. Now Lessig’s middle-class teen can broadcast him- or herself to millions with a few clicks of a mouse.

In a 2008 address to the Library of Congress, Michael Wesch, a cultural anthropology professor at Kansas State University, illustrated the expanding power of personal publishing and broadcasting. He noted that the three major U.S. television networks, broadcasting 24 hours a day for 60 years had aired 1.5 million hours of programming. “But YouTube produced more in the last six months,” he said. “And they did it without producers, they did it just with people like you and me and anybody who has ever uploaded anything to YouTube.” In the 21st century it is amateur publication, not amateur production that is the game changer. The high price of entry is gone, and mass media dominance of published content might never come back.

Oddly, the model for how Hollywood could embrace the move back to amateur contribution and build engagement with fans came from the heart of the 20th century media machine. Starting in 1977 Star Wars captured the imaginations of millions of would-be Jedi knights first through an approachable and classically structured story, and then through books, comics, animated films, games and toys intended only to maximize profits. These extensions, however, helped encourage fan immersion and involvement. Unintentionally, Lucasfilm set the stage for a highly successful transmedia franchise. Only reluctantly have they let some of the reins of storytelling pass out of their direct control.

Oddly, the model for how Hollywood could embrace the move back to amateur contribution and build engagement with fans came from the heart of the 20th century media machine. Starting in 1977 Star Wars captured the imaginations of millions of would-be Jedi knights first through an approachable and classically structured story, and then through books, comics, animated films, games and toys intended only to maximize profits. These extensions, however, helped encourage fan immersion and involvement. Unintentionally, Lucasfilm set the stage for a highly successful transmedia franchise. Only reluctantly have they let some of the reins of storytelling pass out of their direct control.

Wired magazine contributing editor Frank Rose illustrates the influence the Star Wars franchise had on the current generation of game producers, filmmakers and transmedia content producers. Will Wright, the creator of The Sims, a life simulation computer game first released in 2000, told Rose about the franchise’s appeal:

You’ve got lightsabers and the Death Star and the Force and all this stuff that leads to a wide variety of play experiences. I can go have lightsaber battles with my friend. I can play a game about blowing up the Death Star. I can have a unique experience and come back and tell you a story about what happened. The best stories lead to the widest variety of play, and the best play leads to the most story. I think they’re two sides of the same coin.

That play and the imagination of fans did lead to stories. By the mid-1980s the appeal of the Star Wars universe gave rise to fanzines produced on Xerox machines and distributed by hand. The perceived “problem” fell to Lucasfilm’s general counsel Howard Roffman. “You’ve stimulated these people’s imaginations, and now they want to express themselves,” he told Rose in an interview. “But that expression very often finds itself becoming copyright infringement. I would have a parade of people coming into my office in all kinds of tizzies — ‘Oh my God, they’re showing Han Solo and Princess Leia screwing!’ I tried to be the voice of reason — how much damage can it do? But we did draw the line at pornography.”

Initially, expansion of the Star Wars saga was difficult to control even within the official licensed production. Rose notes that a Marvel comic added a giant bunny to the storyline. A 1978 novel described Luke Skywalker becoming physically affectionate with Princess Leia, who five years later in Return of the Jedi would be revealed to be his twin sister.

Initially, expansion of the Star Wars saga was difficult to control even within the official licensed production. Rose notes that a Marvel comic added a giant bunny to the storyline. A 1978 novel described Luke Skywalker becoming physically affectionate with Princess Leia, who five years later in Return of the Jedi would be revealed to be his twin sister.

Roffman, Rose notes, set a new ground rule for the franchise: “From now on, any new installment of the Star Wars saga would have to respect what had come before. With Roffman’s decree,” he adds, “Lucasfilm not only found the instrument that would help reinvigorate the Star Wars franchise; it also created the prototype for the kind of deep, multilayered storytelling that’s emerging today.”

“George created a very well-defined universe,“ Roffman told Rose. “But the movies tell a narrow slice of the story. You can engage on a simplistic level — but if you want to drill down, it’s infinitely deep.”

In the intervening decades, transmedia producers who grew up playing with Star Wars action figures and dueling with toy lightsabers look for the engagement created by Lucas’ story and hope to engineer similar story expansion, expression and play from fans. In 2010 the Producers Guild of America officially sanctioned the title of Transmedia Producer, opening the door for practitioners to earn title credits and entertainment industry recognition. The effort to secure the title was spearheaded by noted transmedia producer Jeff Gomez, of Starlight Runner Entertainment, who in response told Web publication Tubefilter: “This credit will help move transmedia storytelling from methodology to art form, from marketing tool to a conduit for dialog, mutual expression and co-creation. The credit will empower producers and creators, allowing them to take equity in the worlds they’ve worked so hard to build, even as they move like quicksilver across a dozen media platforms.”

Next Page: Transmedia Principles

March 13th, 2013 at 1:06 pm

Here is an example of a Mythical Creation Story for the Cybernetic Age.

“A Dance at the Dawn of Consciousness” starring the Fawn, the Faun, and a Jaunty Unicorn, with special guest appearance of the Noughty Bit playing the inevitable roll of the heavy heavy heart, plus plenty of oderous and amusing hot cross puns.

http://www.musenet.org/orenda/noughty.html

January 22nd, 2014 at 3:38 am

Excellent post that expands my understanding of TMST beyond that of digital age phenomena to perhaps the most fundamental building block of human experience. Even in the simplest phrase one communicates via sound, image, motion, and touch. Hearing a story I then text a friend, or post a photo that represents my thought. From a branding perspective TMST increases stickiness. Reading bed time stories Cat” we see the pictures, listen to the music/narration, and act out the story with the animals. This media enhances the experience and imagination when done well vs. stifling or narrowing in a purely passive experience. Thank you for sharing and I am no seeing many more of my experiences as transmedia.