Exposition: Characters and setting on the streets of Havana. © Kevin Moloney, 2019

Last week revolutionary documentary photographer Robert Frank died. Though this post is going to be about how images tell stories, I keep going back to a quote from this irascible critic of midcentury America. In a New York Times appreciation Arthur Lubow wrote, “Mr. Frank chafed like a bridled horse at conforming to a preordained narrative — as he phrased it, ‘those goddamned stories with a beginning and an end.’”

With a camera Frank was a poet of the real, who photographed like his friends Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg wrote. But a story doesn’t need to be explicit to be a story. We gain as much from what is implied as we do from what is explained. “When people look at my pictures I want them to feel the way they do when they want to read a line of a poem twice,” Frank told LIFE magazine back in 1951, on winning second place in the magazine’s young photographer contest.

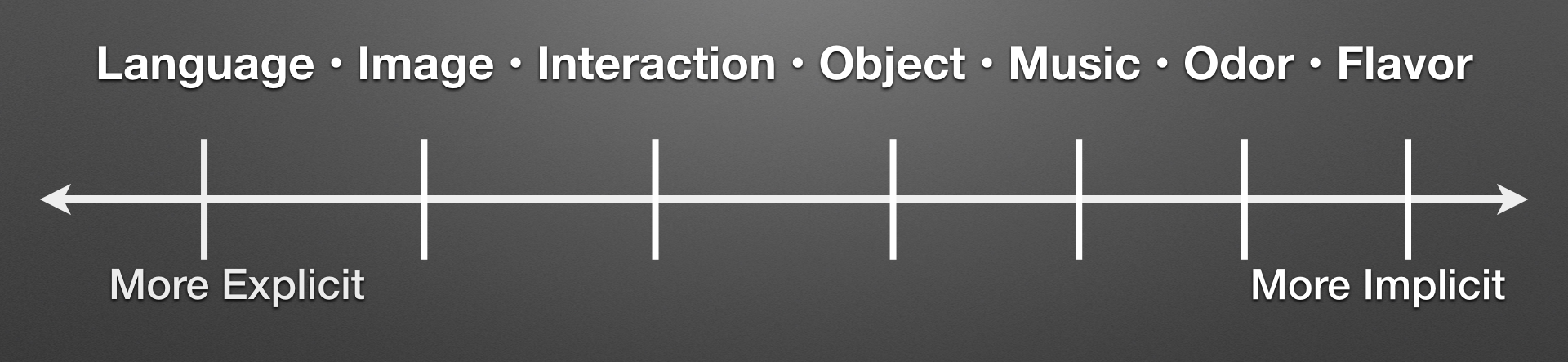

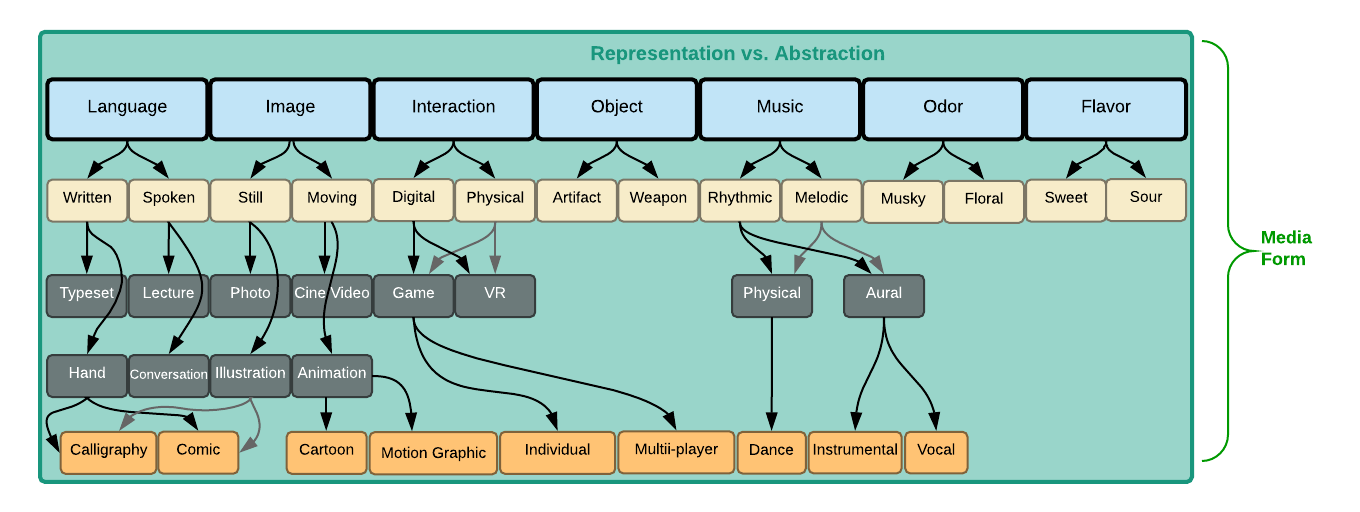

This post continues the expansion of ideas on media form discussed in my recently published paper that breaks ideas of media into taxonomic ranks. When we better define the building blocks, we can more decisively build effective media. In those ranks I identify seven umbrella categories of media form: language, image, interaction, object, music, odor, and flavor. The last post expanded on language. This one expands on image.

Images are often explicit communicators — explicit enough for courtroom evidence, as documentation, or as representation. The photographs against which Robert Frank chafed not only represent the world like a list of facts, but also when combined in series they can be arranged with a beginning, middle, and end.

High-speed series of images — cinema, video — are exceptional at developing a narrative arc, and when combined with language as dialogue, narration, subtitle or interstitial texts, push further toward the complete narrative than language or image do alone.

Alone, however, images are naturally less explicit than language is when it is alone. Sensory information, contexts, events leading up to and resulting from the moment depicted are weak or absent. This requires us to imagine what is missing or add it in, consciously or unconsciously, through a prior understanding of context. The information or the story are implied, and we complete them with our own building blocks.

Creators of the many sub-forms of image — media like illustration, painting, comics, photography, cinema, animation, video, graphics, graffiti, and more — all engage unique tools to communicate explicitly and implicitly, and to mitigate the limits of their medium. In his book, Understanding Comics, Scott McLeod describes how we assemble a timeline between the fractured narrative of panel comics. The phenomenon of “closure” occurs when we imagine what happens between the panels to complete the story. By placing those panels in series, the author implies that they are connected. We do the rest.

This phenomenon also happens with still photographs and other media forms where images appear in series with wide gaps between the events depicted. This happens with cinema, video, and even text when edits jump forward to compress time.

Climax: Beach play in Punta del Este, Uruguay. © Kevin Moloney, 2019

More than a century ago Gustav Freytag described the dramatic pyramid (also often described as the dramatic arc), a classical structure starting with an exposition during which we meet characters and understand setting. It then moves up the side of the pyramid in the rising action phase during which protagonists and antagonists come into conflict. The pyramid peaks at the climax when the clash or cataclysm erupt. Then it drops into falling action as the old situation unravels, and finally the dénouement, or “new normal,” when we understand how the storyworld has changed.

Series of images in comics, photos, and film can hit all these points on the pyramid, or the hero’s journey, or a thesis argument structure, or others. This somewhat explicit arrangement limits how much imagining we do to get from one stage of a story or argument to the next.

Falling action: Hurricane displacement in Florida. © Kevin Moloney, 2019

A single still image presents a different communication challenge (or opportunity depending on the creator’s goal). A painted, drawn, assembled, or photographed image is often only one point on the dramatic pyramid leaving all of the rest of the story to be imagined or assumed, built from learned context or naked assumption. They may be exposition in the case of a portrait or a landscape, leaving us to imagine where the character might go or what will happen in that setting. It could be rising action, showing a tense, pregnant moment or situation. Many — particularly in my profession of photojournalism — are the moment of climax, allowing us to imagine how the moment came to be or how the aftermath will settle. I leave how images can land on the other two to your imagination.

Multiple stages of a narrative in one frame: Pumping water in Burkina Faso. © Kevin Moloney, 2019

Artists have long pushed against the still image as a singular moment, working to convey a sense of time passing or the context of the story or argument they wish to present. By including multiple moments in a single image, she may show different stages of the story in one frame. As the reader digests each of those moments he may experience the passing of time by reading multiple actions one by one.

Rising action and explicit emotion: A combat medic and his wife say goodbye before deployment to the Persian Gulf. © Kevin Moloney, 2019

As the seven umbrella media forms I described in a prior post move from left to right, they also seize emotion as a tool. Language is certainly capable of conveying the emotion of a subject or engaging the emotion of a reader, but its greater strength is communicating the invisible. Successful images all work predominantly on an emotional level. The purely factual ones are usually pretty boring.

For humans, no communication is purely explicit. We always bring something of our own to the media with which we engage. Robert Frank embraced the image as a seed for our own contexts and emotions. His images ignore the story arc in favor of the argument or the poetic stanza. They draw from us readers emotional responses to the limited set of acute facts present in them. His masterwork The Americans first angered us here with what seemed an accusation that we were not who we thought we were. Now 60 years later those images imply something else to us Americans: that we are evolving or learning; the sadness of an acceptance of imperfection; that we really haven’t evolved or learned anything. As will all poets, he showed us who we are, and that is different with each reading.

For further reading see my chapter “Transmedia Photography” in Matthew Freeman and Renira Gambarato’s invaluable The Routledge Companion to Transmedia Studies, 2019.