Media is a mess.

Yes, that socio-political entity, “The Media,” certainly faces some troubles right now. But I’m talking about the contemporary English word itself. It’s messy. It can mean all sorts of things from the goo in a petri dish to the dab on an artist’s pallet. It’s a vocal stop in music and an ancient Persian empire. And it’s also the means, modes or technologies of communication. It’s so messy that even when we write or talk about that last one, understanding of the word is situated in the experience of the listener or reader. It might mean something different to them than it does to you.

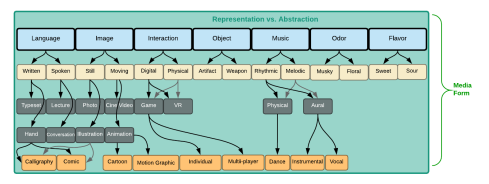

My latest academic article, “Proposing a Practical Media Taxonomy for Complex Media Production,” tackles this messiness by breaking that one word apart under three umbrella categories: Content, Media Form and Media Channel. I started down this road on this blog a few years ago, using these terms to clearly define the difference between multimedia, crossmedia and transmedia storytelling. But let’s dig in a little deeper.

Media Form

I’ll come back to content in later posts. First the idea of media form merits some examples for which I didn’t have room in the linked article. Media form, one of the two terms I use to replace the vague and often-conflated singular medium, has been variously described as a language of storytelling, as semiotics, or as modes. The best way to understand what separates it from its partner media channel is that a media form can be published in many different places. The media channel is the place.

For example, text is a media form. It’s common and old (from the dawn of writing) and, as the illustration up top shows, can land almost anywhere. We see text in print, online, in skywriting and graffiti, in tattoos and crawling across the bottom of a cable news broadcast. Word-besotted humans have put it everywhere. The it is the media form, and the where is the media channel.

In my taxonomy I break the idea of media form first into seven umbrella groups: Language, Image, Interaction, Object, Music, Odor and Flavor. That left to right order spreads them across a spectrum of most explicit (language) to most implicit (flavor) in how they communicate. Language is capable of being very explicit in how it communicates, if the circumstances are right. It is capable of great detail and narrative order or disorder. Words — written or spoken — can describe the absence of something where the other media forms cannot. As Sol Worth pointed out, “Pictures can’t say ain’t.”

Language is never completely explicit, though. The reader or listener always brings her or his own experience to understanding a message.

“Gown removed carelessly. Head, less so.” — Joss Whedon

This is a little six-word story by the creator of Buffy the Vampire Slayer. It’s a nice example of how language is an implicit communicator too. When we read that sparse story we fill in all the blanks with our own experiences and remnants of other stories. We abhor the gaps and make up stuff to fill them ourselves.

So yes, language is the most explicit of my seven categories, but that does not mean it is entirely explicit. Nothing achieves that when humans are involved in the communication.

From the umbrella category of Language, my taxonomy creates a structure to break that idea apart into ever-more-specific language forms. It can be written or spoken. Written language can be scribbled, sprayed, puffed into clouds, or set in a type font. Spoken language breaks into conversation, lecture, voice over and more. With each new level of specificity the media form of language finds more and more advantages, more ways of communication, and differentiates what it can or cannot say.

From the umbrella category of Language, my taxonomy creates a structure to break that idea apart into ever-more-specific language forms. It can be written or spoken. Written language can be scribbled, sprayed, puffed into clouds, or set in a type font. Spoken language breaks into conversation, lecture, voice over and more. With each new level of specificity the media form of language finds more and more advantages, more ways of communication, and differentiates what it can or cannot say.

This is where I stop saying ain’t. Up soon: Image.

Leave a comment