I’ve written elsewhere that we’re living through a Cambrian Explosion in the ecology of media. Suddenly — if you think about the last few decades as a fragment of the timeline that stretches back to before cave painting — we can tell stories in so many media forms and on so many media channels that it would make Richard Wagner jealous enough to steal a magic ring. We can make our kunstwerk more gesamt than ever before.

And with this explosion has come a diversity of terms to describe new creations and new arrangements. Multimedia? Crossmedia? Transmedia? What is the difference? I get that question a lot, and it’s a good one.

These three terms can be divided on how they use media form and media channel. Media form is a language a story uses, and it can include text, photographs, illustrations, motion pictures, audio, graphic nonfiction, interactive forms and many others. These forms are then reproduced someplace and that place is a media channel. Journalism channels can include newspapers, magazines, books, television, radio, lectures, museums, game consoles, the Web or a mobile app among many others. There are hundreds of possibilities here.

Multimedia

This is an old term, dating back to before Macintosh computers that smiled at you when you turned them on. Looking for a way to describe the mix of media forms possible in the early digital age we borrowed the term “multimedia.” It spread to journalism production when news first hit the Web. Newspapers in particular grabbed the term to describe telling stories not just with words and still pictures, but also with infographics, sound and then video.

Cinema newsreels and television had been reporting news with text, sound, moving and still images and informational graphics for nearly a century. However, newspapers in the U.S. acted like they had just discovered America. They gave their “discovery” a new name despite the fact that the natives knew it was there all along. “Multimedia” is now applied to almost any kind of digital storytelling.

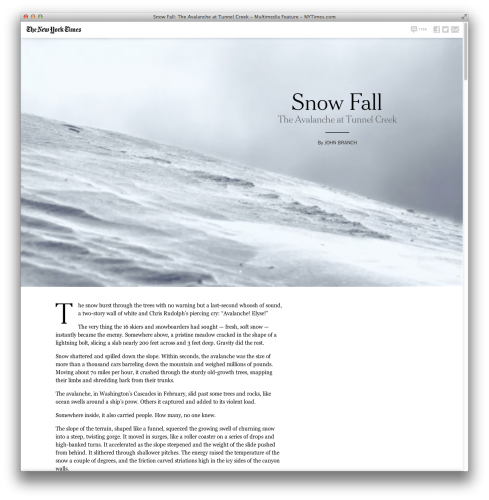

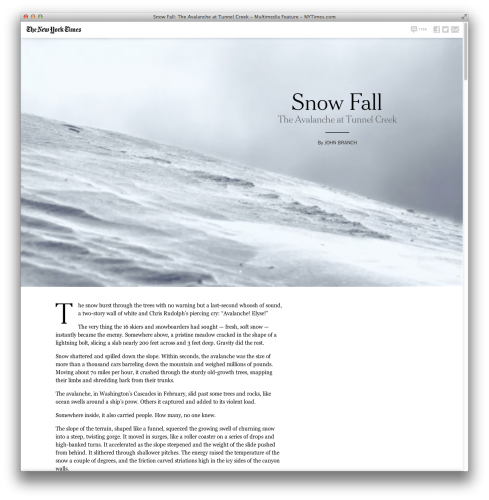

With multimedia you put many forms to work telling the story, and place them all on one channel. Think about a complex Web publication like the New York Times’ now infamous Snowfall: The Avalanche at Tunnel Creek piece. This is a clear example of multimedia storytelling at an advanced state. They use text, photographs, video, maps and interaction to tell that story, but it’s all on one Website. Though it has its weaknesses, Snowfall was so groundbreaking at launch that its name is now a verb. “To snowfall” something is to produce a Web-based story using the same aesthetics, and the Times continues to polish that style with packages like Tomato Can Blues and Extra Virgin Suicide. The Times isn’t alone either. Others like the Seattle Times’ Sea Change are equally impressive examples of multimedia storytelling.

Multimedia = One story, many forms, one channel.

Crossmedia

This is a term that most likely originates in the advertising industry, and it means to tell a story in many different media channels. Coke added “life” to the 1970s on TV, in print and on radio. In journalism you can see very old examples of this in the venerable wire services. Agencies like The Associated Press, Reuters and others distribute a story through multiple newspapers around the world as well as magazines, radio and TV. But it is the same story, the same set of facts in pretty much the same arrangement. The distribution may include text, pictures and video, but they are all telling the same story in the same way.

A few interesting new agencies, like I-News at Rocky Mountain PBS, have tweaked this model on a regional scale to better distribute investigative journalism to  news outlets strapped for cash and reporters. Where multimedia makes use of the different affordances of media form, crossmedia makes use of the different affordances of media channel. Where the use of form in multimedia appeals to the different learning styles or modes of understanding, channel is used in crossmedia to reach a broader audience.

news outlets strapped for cash and reporters. Where multimedia makes use of the different affordances of media form, crossmedia makes use of the different affordances of media channel. Where the use of form in multimedia appeals to the different learning styles or modes of understanding, channel is used in crossmedia to reach a broader audience.

Crossmedia = One story, many channels.

Transmedia

With transmedia we no longer tell just one story. We tell many stories that put the flesh on the bones of a storyworld. In journalism that storyworld may be an important issue, it may be a community or it may even be a reporter’s regular news beat. Each story is complete in and of itself, but many of them taken together expand our understanding of the larger subject.

Multiple stories on an issue or a beat are not new to journalism. But with transmedia storytelling we place those many different stories on different media channels. This broadens the audience the way crossmedia does, and gives us the incredibly valuable ability to target a journalism audience that can best use the information. Advertisers no longer “spray and pray.” They craft their ads for particular audiences and then place them right under the nose of their targets. They build efficient audiences. When that is done well their targeted publics coalesce into a more effective mass audience.

Transmedia storytelling also strives to lengthen engagement with a story by not repeating itself. We tell multiple different stories in varying forms and place them on many channels. In doing so the reader has reason to look at more than one of those stories, hopefully stretching the time they spend in our storyworld. In journalism we want to deepen engagement with the issue at hand. The longer they spend, the more valuable that information may become.

Producing transmedia in journalism requires partnerships and collaboration. Few journalists have all the skills to produce many stories in many forms all by themselves. This is a team effort, and few legacy news companies control more than one or two media channels. To truly target their audiences they will need to collaborate with the owners of other channels in a mutually beneficial manner. Journalism is no stranger to that collaboration either. For example, newspapers and television stations have partnered on stories for decades.

Transmedia = One storyworld, many stories, many forms, many channels.

Multimedia, crossmedia and transmedia are points on a fluid spectrum that blend from one to the next. Every point on that spectrum has a unique storytelling advantage, giving us a very flexible set of tools for 21st-century journalism.